How to create a Theory of Change

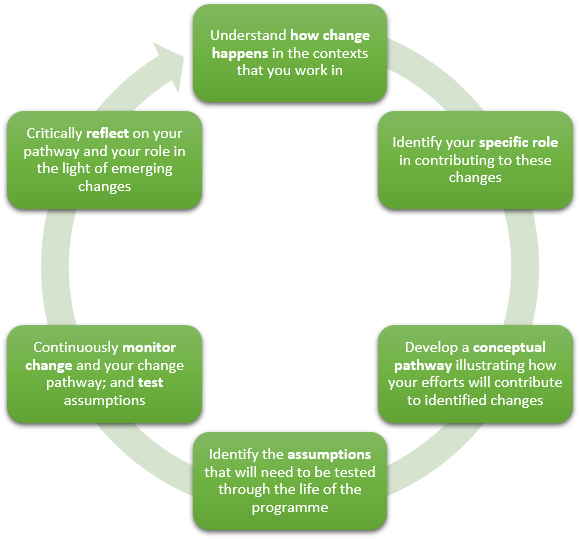

There are many manuals about how to develop a Theory of Change. Here we will follow the 6 steps that Intrac identified based on an analysis of a good number of ToC instruction manuals.

However it is important to note that you are not obliged to do the process in this order. Below we start the process completely from scratch. But often organisations already have many things in place and they start formulating their Theory of Change later on. This is okay, one main principle of ToC is to make the implicit explicit. In fact, evaluators will sometimes stimulate you to formulate the ToC of a programme right at its end, to make the reason (logic) and assumptions behind the intervention visible in order to be able to test the assumptions and the pathway of change.

1. Identify how change happens in a context

There are many ways to bake a pie and there are many ways to achieve change in a particular context. This is not so much a matter of the right way and the wrong way. Instead it is about identifying the possible strategies to achieve the change that we seek and – importantly – to make our own choices in this matter explicit. This means that you need to develop a thorough understanding of the situation and how different parties interact.

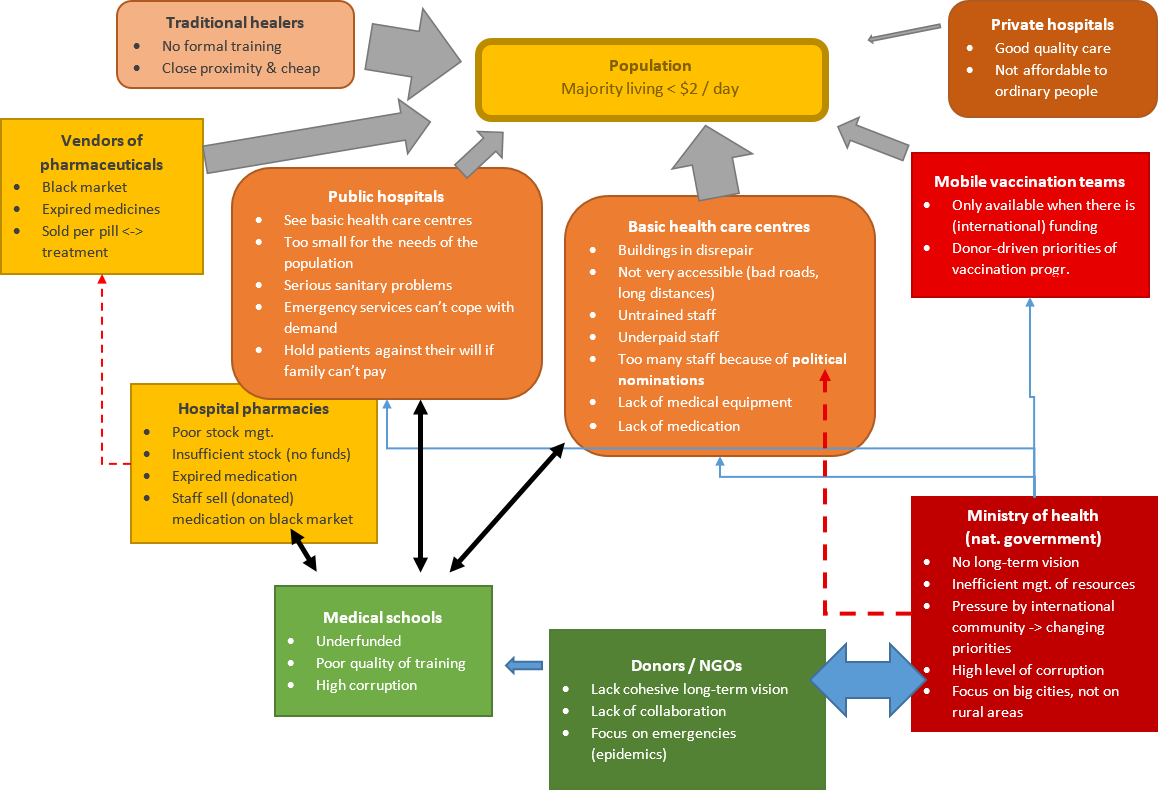

- Who are the different actors that can influence the situation, either in a positive or in a negative way? In other words what are the different forces that have the potential to help achieve the outcomes? Each organisation has its own focus and identity, but many share values, attitudes, relationships, actions and objectives (in line with the outcomes that you will identify). Not all actors will have a positive influence on the desired outcomes and change, so it’s important to identify potential ‘adversaries’ as well and make plans on how to reduce their influence. Alternatively, you could work on changing their attitudes.

- What are the factors in the context that could have a positive or negative influence on the desired change?

- What or who needs to change (targets) and in what timeframe?

Improving your understanding on how change happens can come from discussions within your organisation (making implicit knowledge visible) and with others, from documentation and public sources, from research, from participatory analysis with stakeholders/beneficiaries (workshops, interviews, surveys…) and other approaches.

With the information about the different stakeholders, forces and influences you can create a System Map. This kind of mapping not only allows you to identify who does what, but also to understand how the different forces interact within the context.

2. Identify your own role

The system map will help you to identify the organisations or actors that also work on the outcomes that you want to realise. In many cases your organisation on its own will not be able to achieve all necessary outcomes and achieve the durable change of the long-term goal(s). So what can your organisation do, given its strategic focus, expertise, resources, etc. and what can others do? What kind of working relationships (partnerships) could we establish with certain parties so we can focus on what we do best and together reach the desired outcomes and change?

Partnership or collaboration are the most direct and active ways to work with others, but not all relationships will necessarily have this level of involvement. In many cases it is more a matter of aligning your interventions with those of other actors.

3. Develop a conceptual pathway – the Theory of Action

Once it’s clear how change could happen within a certain context – the Theory of Change – it’s time to identify what you as an organisation are going to do to support that change: the Theory of Action.

Some manuals describe the following steps as something you do with your own team. However if you really want a solid ToC it’s much better to see this as a participatory exercise. Seek the involvement of different partners and stakeholders (including potential beneficiaries). Find a good facilitator, organise one or more workshops and allow for discussion (rather than sending documents around by email).

A] Identify long term goal(s)

The first step in developing the pathway to change is to identify the change that you want to achieve. This is your long-term goal. It is a vision of success that you create together with your staff and other stakeholders. But this vision is not just a beautiful dream: it has to be firmly grounded in reality. It has to describe real people, real situations, real cultures, real organisations, etc. It has to be plausible, not some kind of utopia.

You can have more than one long term goal, but if you have more than one goal you will quickly end up with a very large number of outcomes that all have their relations and assumptions and you will end up with a big giant ToC that no-one understands (so KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid).

To clarify this vision or long term goal, you can describe what the desired change in behaviours, attitudes, capabilities, values and/or relationships will be.

Because the situation in which you work changes over time, your vision also has to by dynamic. This means that working together with other key actors you will need to solve new problems that occur and modify your approach were necessary.

B] Mapping and connecting outcomes (conditions)

The next step is to identify the key changes that are needed to achieve this goal. This is sometimes called mapping. The key changes are the conditions (or outcomes) that must be in place for the change to occur. Explain for each condition/outcome why it is necessary to achieve the goal(s).

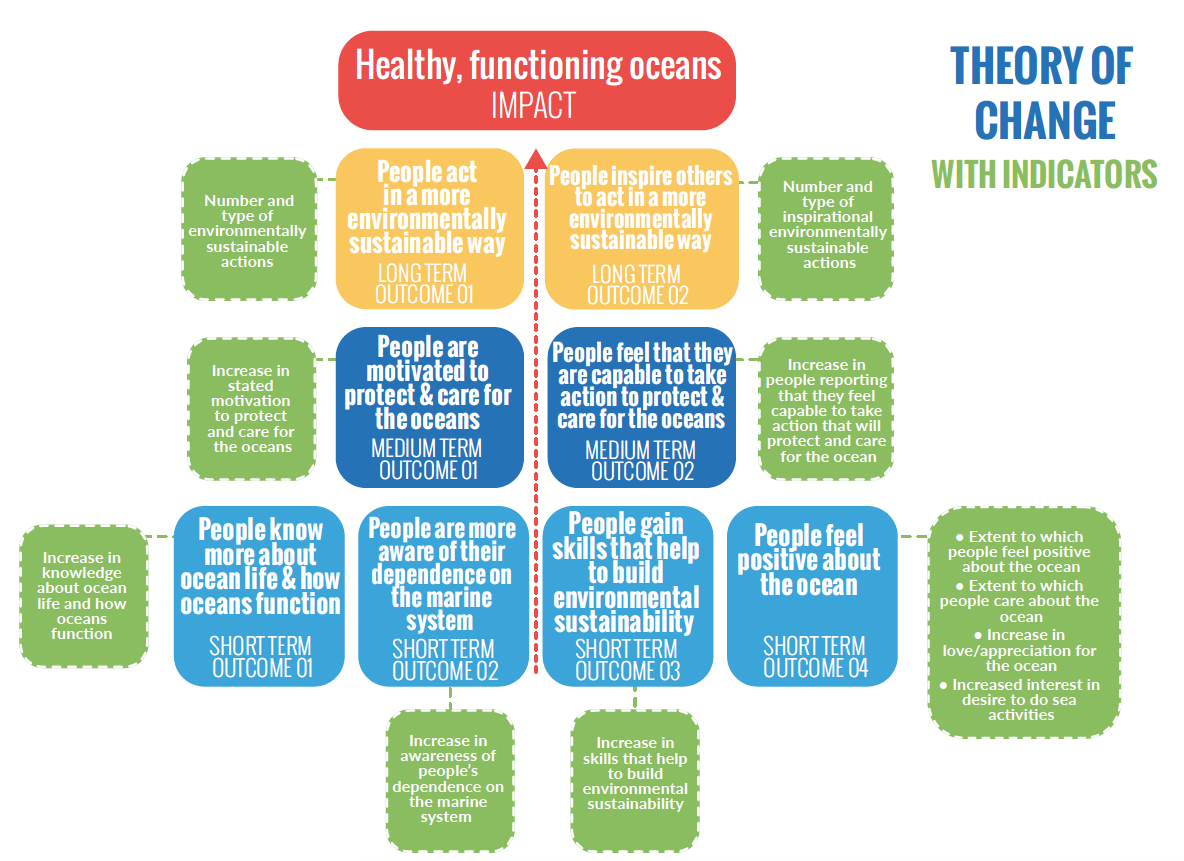

These outcomes are not separated building blocks: they can have all sorts of relationships between them, which you must identify. For one thing, it will take more or less time to achieve certain outcomes. That is why the technique of backwards mapping is often used: starting from the final goal(s) you can identify the long term outcomes, then the intermediate outcomes and finally the early term outcomes.

Make sure that you identify the changes that must take place to achieve the long term goal(s). Don’t lose yourself in a wish-list of ‘nice-to-have’ changes but focus on outcomes that are essential for long-term success and on the main topic. Resist the temptation to include all kinds of related topics and to try and solve any kind of problem that you encounter in a given setting or context.

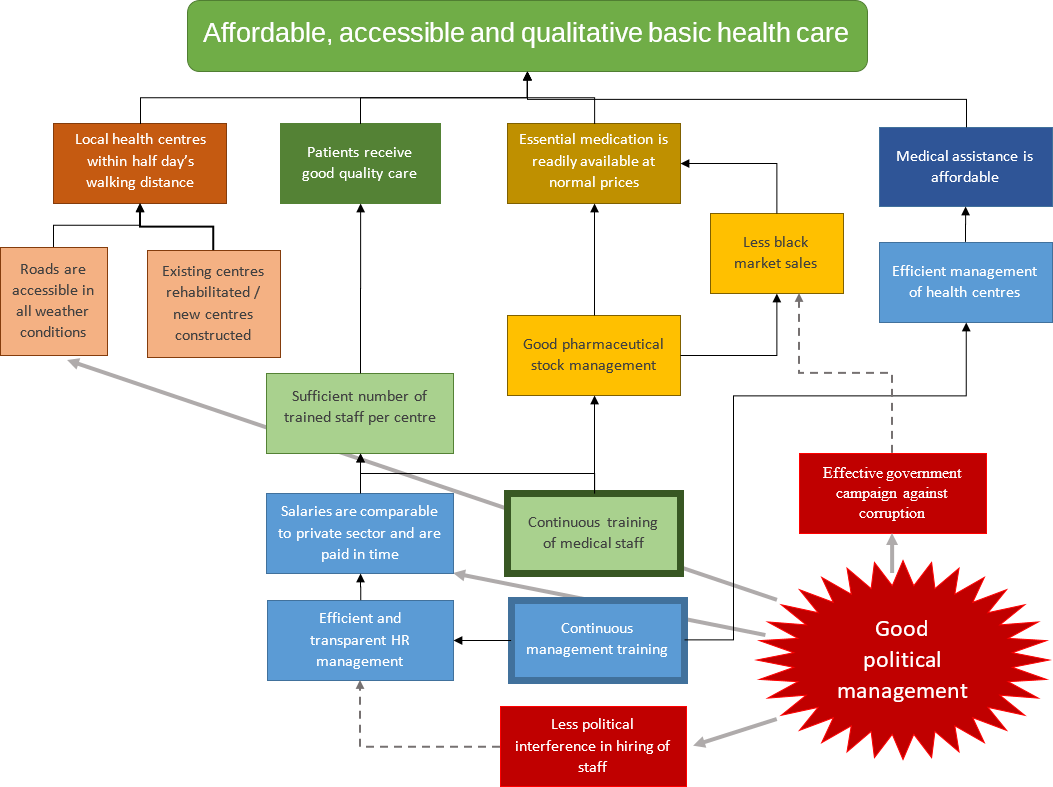

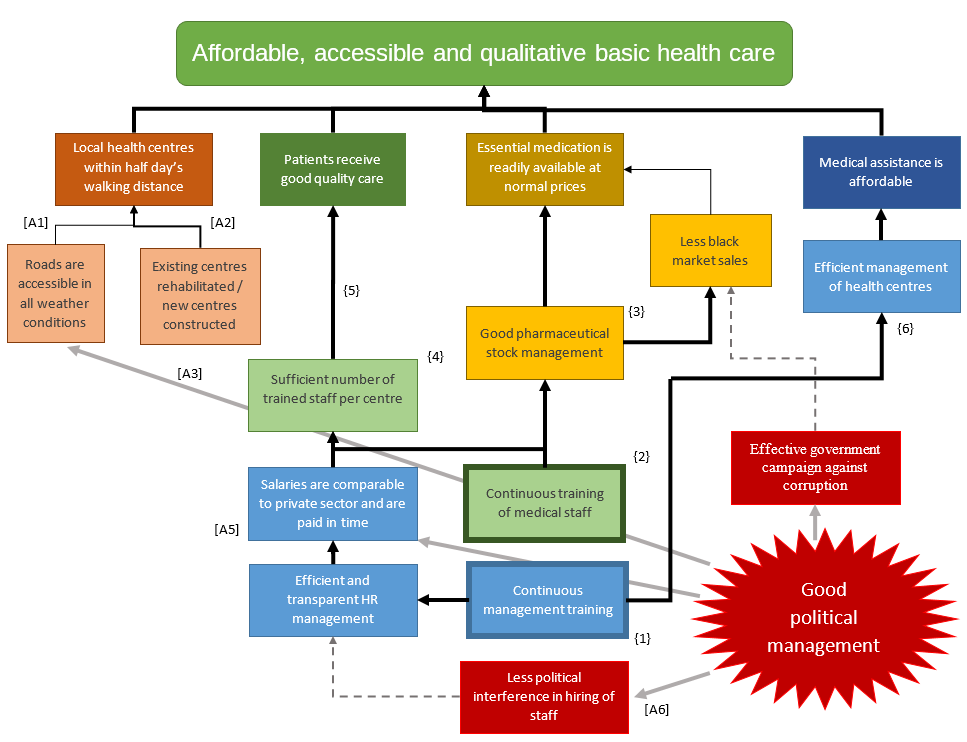

Through this process you will get an overview (or chart) with the outcomes and their connections, which is called the Pathway of Change (or Conceptual Pathway). You will probably start with a first draft that you’ll refine gradually, so this is kind of a gradual process. And even later on when you’re already executing your vision you will need to update the pathway of change.

Once you have this overview, it’s also important to think about who can do what. More often than not your organisation will not be able to achieve all the outcomes on its own. So who can contribute to these outcomes? And how can we collaborate with others to achieve the final goal(s)?

C] Identify possible interventions/activities

Once all the outcomes and their relations have been identified, you can reflect on what activities, approaches or interventions are needed to achieve each outcome. At this stage it is more about the type of activity or intervention; there is no need to go into detailed planning of interventions yet.

However it is important to get to clearly defined outcomes at this stage:

- What does success look like? On what scale will you be working (national, regional, local)? You have to specify the range and scope. Success may have a material form, but more often than not it is a question of people. This means that success may not be physically tangible but that it may be a question of changed behaviours, attitudes, beliefs, values, etc.

- Who is the target population? Whose situation will change when this outcome is achieved? Who will benefit from the intervention(s)? Who are the key constituents?

- What is the expected timeframe? This depends on the time it will take to for the intervention to achieve the desired change, but also on the relation between each outcome and possible others. It may well be that other outcomes must be achieved before this one.

- What amount of change is necessary for success? More often than not this is not a simple yes/no or all-or-nothing answer. If the desired outcome is that the women of a region or country are literate (with the goal of reducing discrimination against women for instance), how many women have to be trained before you have a critical mass that is sufficiently large to speak of success (and sustainability)? Ten women is clearly not enough, but even in the most developed nations there is never 100% literacy. Here the reflection is not so much about numbers (that is what indicators are for and we’ll get back to that) but more about how the (durable) change will look like that a programme should be able to achieve.

This process will give you a first version of a diagram or map with the outcomes, activities and their relations. As explained before you’ll have to go through several cycles of refinement, revision and adaptation with different stakeholders to get to a final version.

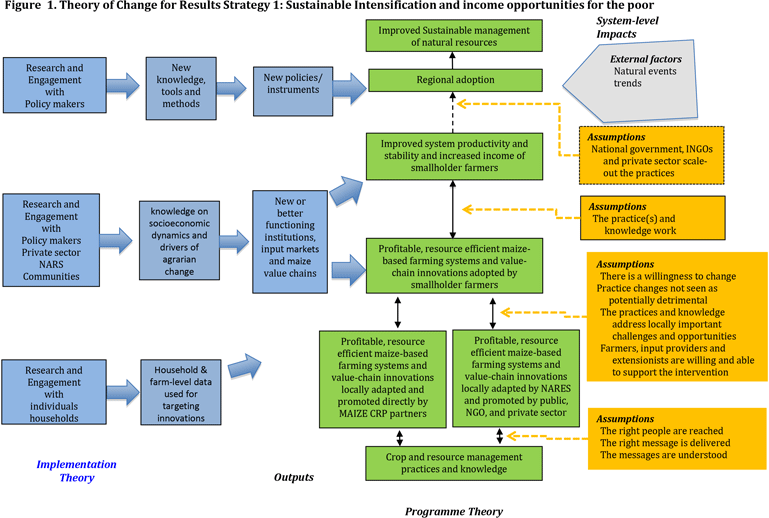

In the ToC example above, the contribution of the organisation to the overall change process is marked with the thick black arrows. In the middle, the main intervention strategies are in the boxes with the thick edges: 'Continuous training of medical staff' and 'Continuous management' training respectively. The main assumption here is 'Good political management' which will have to reduce political meddling in nominations of doctors and other medical staff and create a real motivation to work on infrastructure, fight corruption and so on. This assumption must be elaborated and clarified in the next step.

The main purpose of this diagram is that it provides a good and understandable overview of your Theory of Change. You can use all kinds of visual aids (colours, pictograms, arrows…) to accomplish this. And yes, in some cases your ToC will resemble a certain figure and you can emphasise this and release your inner creative person. But don’t force it, don’t make the message secondary to the artwork and don’t simplify too much or modify the content to fit into your beautiful artwork.

In your narrative document, it’s important to explain the rationale of your ToC: why are the different outcomes needed to achieve the overall goal and why will the different interventions lead to the achievement of the outcomes and final goal(s)?

4. Identify the assumptions

Assumptions are rules of thumb that influence our choices. We use these rules of thumb both as individuals and as organisations. When we create our mental picture of how change is going to happen, we make a number of assumptions about the situation (context) and how people and organisations are going to act and behave. These are called contextual factors. But we also make assumptions about the Pathway of Change that we are designing:

- We assume that all existing conditions (outcomes) have been identified

- We make assumptions about the connections between the outcomes and how they can be achieved in the short/intermediate/long term.

- We assume that the planned interventions will lead to the desired outcomes.

We have to make the assumptions explicit, so that they can be debated, enriched and checked (by us before we start to do things or by evaluators in the course of an intervention or thereafter.

So listing the assumptions is not enough: it is important to test them – not just at the design phase but throughout the lifetime of the Theory of Change. This is why the identification of the assumptions is important, because then we can verify if they hold true. If they don’t, we will need to update our ToC and adapt or increase our interventions.

Together, the conceptual pathway / Theory of Action and the assumptions make sure that the ToC can be tested and validated or disproved (partially or as a whole). Evaluators can verify to what degree the outcomes are achieved, whether the assumptions hold true and whether the theory as a whole leads to the achievement (or contributes to) of the end goal.

The result of this (initial) process is:

- the Theory of Change diagram: in some cases the reality is so complicated that a single diagram becomes too complex. So organisations sometimes use different diagrams or in some cases don’t bother with the diagram and only use a narrative document.

- a narrative document that describes the expected story about how change is going to happen. It also explains and details the different elements of the Theory of Change.

5. Monitor change

Knowing if change actually takes place – and taking action by modifying your intervention(s) where necessary – is an important part of ToC thinking. Together with regular testing of assumptions this is also what makes ToC more of a process than just a product in terms of a diagram and a narrative document.

The focus of monitoring is not so much on the intervention itself, but on seeing whether the desired change as described by the outcomes really takes place. If you have a ToC that has identified outcomes on the short, the intermediate and the long term, you can identify indicators on these different levels. As the scope of this change is often larger than the organisation’s outreach (the organisation contributes to change; it cannot entirely be attributed to what the organisation did), monitoring is not so much about the follow-up of activities or measuring outputs. Instead this is more impact monitoring or impact assessment, that often involves information from different actors and sources outside the organisation. That doesn’t necessarily mean that information gathering has to be complex and depend on large scale surveys.

Because your organisation generally only has a specific contribution in the achievement of certain outcomes and the realisation of the final goal, certain things will be under your control and others won’t be. This means that it makes sense to focus your monitoring efforts on the effects that are more or less under your control. Sometimes this is indicated in the ToC chart with a line that indicates the accountability ceiling, or with different areas that indicate your sphere of control, your sphere of influence and your sphere of interest. Of course this doesn’t mean that you are not interested in information about outcomes or context factors that lie outside your control/influence.

The monitoring of change goes hand in hand with the examination of the assumptions. Do they still hold true or not? Does change at one level of the pathway of change indeed support change on a higher level? If this is not the case then the assumption may be false.

6. Critical reflection

The reason for this regular monitoring and evaluation is not to produce reports – for donors or for management – but to re-examine the strategy and programmes from time to time. During this reflection, the following questions can help you along (Intrac, 2017):

- Is the Theory of Change still valid?

- Is the organisation / programme working with the right people in the right way?

- To what extent have anticipated changes led to changes in the lives of targeted populations?

- What is now better understood than before?

- What needs to change in the understanding of how change happens, or an organisation or programme’s specific role within that?

The organisation must use the lessons from this reflection to act and to adapt the intervention(s), assumptions, strategy and so on.