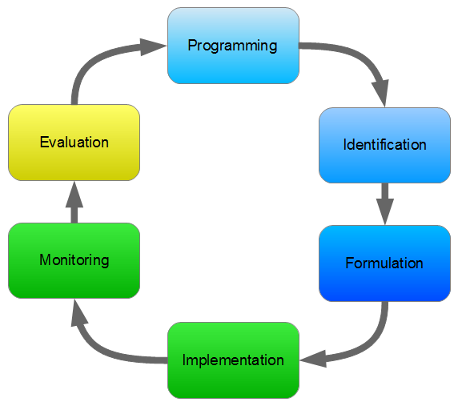

The Project Cycle

In its basic form, the Project Cycle counts six phases. However, as some donor agencies, NGOs and consulting firms tend to bring out their own versions, this number of phases and their content may vary.

The phases are:

Often, implementation and monitoring are combined in one step. Some donor agencies add an additional step of ‘Financing’ or ‘Approval of the proposal’ between ‘Formulation’ and ‘Implementation’. From the point of view of the NGOs that want to introduce a project, negotiating or lobbying is another step that could be added between programming and identification or between identification and formulation.

The first three steps can be seen as the design phase of the project. This can easily take up to two years before the final approval is given and work (or practical preparations) can begin. The duration of the project itself depends on its activities and the needs of the beneficiaries, but more often than not also on budgetary restraints or the regulatory framework of the donor. That is why consecutive projects (sometimes called actions) are combined into a larger programme. Again, in such a programme it is important to learn from previous actions, but in reality this may not always be the case (or only to a limited extent).

Programming

The programming phase establishes the link between the individual project and the overall strategy of the organisation. How does the NGO or development actor want to realise the main purpose of the organisation (as expressed in its vision and mission for instance) over the next couple of years? To answer this question, many organisations go through a participatory process with their beneficiaries and with other stakeholders. This often leads to some kind of long term strategy document, that contains general orientations about what activities and projects the organisation will do, in which countries or regions, with what target groups and counting on what means (own resources, donor funding, etc.)

The programming phase establishes the link between the individual project and the overall strategy of the organisation. How does the NGO or development actor want to realise the main purpose of the organisation (as expressed in its vision and mission for instance) over the next couple of years? To answer this question, many organisations go through a participatory process with their beneficiaries and with other stakeholders. This often leads to some kind of long term strategy document, that contains general orientations about what activities and projects the organisation will do, in which countries or regions, with what target groups and counting on what means (own resources, donor funding, etc.)

Some organisations limit this reflection to their activities in the field. Other take a step further and develop a long term vision for all aspects of their work: human resources management, financial management, quality management, external communications strategy, lobbying strategy and so on.

Often, the organisation’s strategy will fit into a broader vision, for instance common policies developed with the NGO sector in your country. This may also lead to specific thematic or country policies that are added to the overall strategy and that explain how the organisation will implement these policies over the next couple of years (for instance a gender strategy, a food security strategy, a country strategy, an ecological durability strategy, etc.)

At this step, the organisation may also develop common tools or approaches that will be used in the coming years. These may include practical guidelines that can be used for the different projects, or lists with criteria (for instance for the selection of partner organisations or beneficiaries) and other tools.

All this doesn’t come out of the blue. The idea behind the project cycle is that these reflections are fed by the lessons learned from previous projects, amongst other things through evaluations but also by asking those who were involved to participate in this phase.

Identification

In this step, the idea for the project is initiated and the organisation verifies whether this idea really responds to the needs of the (future) beneficiaries. In other words, the pertinence of the project is checked. This means that we have to see if it fits our strategy on the one hand. But more importantly it has to be based on a thorough knowledge and analysis of the situation in the target zone/country and of the needs of the beneficiaries. This is where the expertise of the local partners comes in – generally to guarantee the quality of the project, it is expected that the project is formulated together with the local partners.

In this step, the idea for the project is initiated and the organisation verifies whether this idea really responds to the needs of the (future) beneficiaries. In other words, the pertinence of the project is checked. This means that we have to see if it fits our strategy on the one hand. But more importantly it has to be based on a thorough knowledge and analysis of the situation in the target zone/country and of the needs of the beneficiaries. This is where the expertise of the local partners comes in – generally to guarantee the quality of the project, it is expected that the project is formulated together with the local partners.

As a result of this phase, an initial draft of the project is elaborated which contains all elements of the intervention logic:

- What activities do we want to do?

- To achieve what tangible results (outputs)?

- To remedy what situation? Why do we do this project? In other words what is the purpose of our project?

- How will our project contribute to improving the overall situation in the intervention area? What will the impact be in the long run?

In other words, the first column of the logical framework is elaborated. In PCM – as in the logical framework approach – the idea is that there is a cause-and-result chain. The activities lead to the tangible outputs, and through the combination of these outputs we will realise the purpose of our project.

At this stage, we also have a look at the resources we will need and try to estimate what the overall budget of the project will be.

Often this project draft must go through an approval procedure within the organisation, meaning that the director, the executive board or some form of a project committee will have to scrutinise the project and give their approval.

Formulation

Once the basic concept of the project is determined and approved, it is time to go into detail. Often, this comes down to writing a detailed project proposal. In the concept of PCM, models are used for establishing:

Once the basic concept of the project is determined and approved, it is time to go into detail. Often, this comes down to writing a detailed project proposal. In the concept of PCM, models are used for establishing:

- The narrative proposal, which gives an overview of the project and explains in detail:

- What the situation is of the target groups in the area of intervention/country;

- Who the partners are;

- What the objectives are;

- How the objectives fit in the donor’s policy/the country development strategy;

- What activities will be executed;

- What the risks are and how they will be dealt with;

- How the partners will collaborate with local authorities and other stakeholders

- The budget proposal, detailing every expense and sometimes regrouping them per activity or output

- The logical framework of the project

- A detailed planning of the activities

- Other documents to explain how the organisation manages its projects, such as partner identification forms, registration forms for beneficiaries and target groups, the official NGO registration and so on.

Sometimes the NGO has (and is allowed to use) its own models, but often donor agencies will oblige NGOs to use their templates.

Often these templates help the organisation to really think the whole project through and to conceive of every detail. On the other hand, the amount of detail that is sometimes requested can be overwhelming and very often the same information has to be repeated over and over again between projects – which again goes against the idea of continuity and learning. But with all this information, the partner organisations will get a good idea of the viability of the project and any pitfalls that may be on the road.

It is at this stage that we can integrate the whole logical framework approach as a participatory approach to determine the various elements of the project:

- Validating and detailing every element of the intervention logic (first column of the logframe)

- Thinking about how the project will be monitored and evaluated (second and third columns of the logframe).

- Reflecting about risks and assumptions (fourth column), and how to deal with problems should they occur (and what their possible impact will be).

- Practical organisation like who does what and when? How will the communication and reporting be organised? Who is responsible for what?

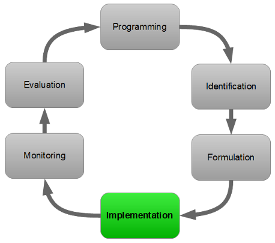

Implementation

Once funding is secured, there is nothing to stop us from executing the project (although ‘nothing’ may be too optimistic sometimes). At this step, we can start with the practical preparations of our project: recruiting additional staff; organising the project team at different levels and locations; setting up logistics and purchasing new equipment; introducing ourselves and the project to the people, the media, the local authorities, the representatives of international organisations and so on.

Once funding is secured, there is nothing to stop us from executing the project (although ‘nothing’ may be too optimistic sometimes). At this step, we can start with the practical preparations of our project: recruiting additional staff; organising the project team at different levels and locations; setting up logistics and purchasing new equipment; introducing ourselves and the project to the people, the media, the local authorities, the representatives of international organisations and so on.

The monitoring and accountability system has to be put in place too. This includes the system for financial management and reporting; the system to monitor the execution and results of our activities; the administrative management system; the risk monitoring system and emergency handling system; and the planning of financial audits and (external evaluations).

At this point in time, the situation of the beneficiaries is measured before the activities start, using the indicators. This is known as the baseline, which will serve to compare the evolution of the situation of the beneficiaries to as the project progresses. However, some donors will oblige you to establish a baseline during the formulation phase and incorporate it in the project proposal. Even so, it may be a good idea to establish the situation at the very start of the project, especially when it’s been a while since the baseline was established, because other things may have influenced the beneficiaries’ situation.

The project’s planning that was established during the formulation phase may also need to be updated. It is not rare that a lot of time has passed between the development of this planning and the final approval of the project by the donor. In the meantime the situation may have drastically changed. Experience also shows that it is only now that serious reflection is given to the planning of the activities, as the project team is confronted with the reality and limitations of working in a given setting with certain resources and time available.

Implementation is all about doing the right activities to respond to the actual needs of the beneficiaries. The information you receive from your monitoring system should allow you to respond flexibly to those needs. At least that is the original idea behind the project cycle. In the worst case, you are totally bound by your contract with the donor and obliged to follow it to the letter, even if you know that the situation has changed and that you are not doing the right things. Most donors are open to adapting the original contract in some way, but often within limits. Also, the procedure to change your contract may be cumbersome and slow, and modifying the contract is not something you would go through more than once during the project.

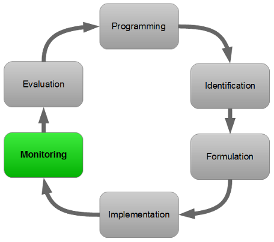

Monitoring

The monitoring and implementation phases are often taken as one because they are so intertwined. In any case it is clear you can’t speak of consecutive phases because they go together. Monitoring is about checking whether your project is going as planned, meaning that:

The monitoring and implementation phases are often taken as one because they are so intertwined. In any case it is clear you can’t speak of consecutive phases because they go together. Monitoring is about checking whether your project is going as planned, meaning that:

- You’re doing the activities according to plan

- You’re getting the outputs that you want

- You’re spending the budget according to plan

Monitoring is not about the fundamentals of your project, i.e. the question whether you’re doing the right things in the first place.

To monitor the project’s outputs, you’re using the indicators of the logframe. To monitor the progress of the activities, you’re using the project’s planning (updated). To monitor expenses, you’re using the project’s accountancy and compare it with the budget.

In the concept of PCM, monitoring is needed to adapt your project flexibly to the ever changing needs and the ever evolving situation in the field. Monitoring should allow you to take project management decisions on the go:

- Change the activities that you do, or change the order of the activities, or put an end to certain activities because they don’t lead to the results that you expected.

- Verify whether outputs are achieved in time, and change priorities and/or reroute resources (staff, finances, equipment…) to make sure they will be achieved.

- Avoid financial mismanagement, or expending too much or too fast. Maybe the cost of certain activities may have to be reviewed and other solutions may have to be found. In other cases the costs will turn out to be lower than expected, and additional activities may be organised to exceed the original objectives of the project.

- Determine whether you should start up a procedure to re-negotiate parts of your contract: because the situation has changed drastically; because risks have materialised and you can’t handle them as you’d hoped; because you’re spending more than expected; because you want to re-allocate your resources; etc.

In this sense, monitoring does not equal controlling. However, in practice the opposite is often true and monitoring becomes something to satisfy the donor and produce the necessary reports in time.

In any case, the information you get from your monitoring system is not only used to manage the project, but also for accountability. There are two kinds of accountability:

- Downward accountability: you use the information from your monitoring system to show the beneficiaries what they’ve achieved so far and how they and their situation have progressed since the beginning of the project. This is also an element of participation and it is important to create ownership of the project and of its results.

- Upward accountability: the information from the monitoring system is used to report to the partners, to ‘headquarters’ and to the donors.

Again in reality, downward accountability is often forgotten, and the emphasis is on reporting to the donor. A lot of time can go into reporting, also because information has to be poured into the formats provided by the donor. This is especially true for financial reporting: an inordinate amount of time can be spent on making sure all tickets and invoices are there and eligible according to the donor; classified and registered in the accountancy system; verified and verified again; audited internally and externally…

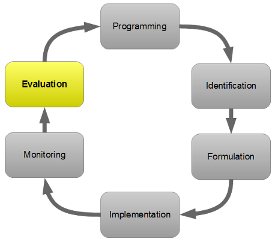

Evaluation

While monitoring is about checking whether the project is executed according to plan, evaluation is about the very reasons why you’ve developed your project in the first place. Do the results of your project effectively lead to the desired change in the lives of your beneficiaries? Was your intervention strategy effective? What are the expected and unexpected effects and impact of your project? What can you learn from the way you organised your activities? What can you learn from your project that you could use for consecutive projects and actions?

While monitoring is about checking whether the project is executed according to plan, evaluation is about the very reasons why you’ve developed your project in the first place. Do the results of your project effectively lead to the desired change in the lives of your beneficiaries? Was your intervention strategy effective? What are the expected and unexpected effects and impact of your project? What can you learn from the way you organised your activities? What can you learn from your project that you could use for consecutive projects and actions?

Evaluations can be:

- Internal evaluations: conducted by the organisation itself.

- External evaluations: conducted by an external evaluator, either an individual or a (specialised) organisation or firm. Often donors will require you to do external evaluations because they are supposedly more independent and reliable. On the other hand, external evaluators may not understand the situation as well as the local staff or partners do. Often, time and financial constraints also weigh on the quality of the evaluation and many evaluators rely heavily on the project team anyway, which beats the point of independency (also in the end it is the NGO that pays the bill).

Projects with a long duration often have mid-term or several intermediary evaluations in addition to the final evaluation. In order to do a good evaluation, the evaluators need access to information from the monitoring system. One of the most common problems is that no baseline situation has been established at the onset of the project, making it difficult to appreciate the evolution of the project and of the situation of the beneficiaries.

In addition to providing an evaluation report, most evaluators will organise a feed-back meeting of some sort. This is important for people to learn about the findings of the evaluation and the good things and bad thing about the project. This way they can take the information along for the next project.