Results Based Management (RBM)

As a next step in the evolution of logical framework approaches, Results Based Management or RBM tries to respond to a number of issues of the PCM and LFA methods. People often ask what the difference is between PCM or LFA and Results Based Management. In a sense, you could say that RBM is PCM done right. It provides more tools and directives on what you should do to ensure that you really design your project in a participatory way, or to make sure that you really think about assumptions and risks.

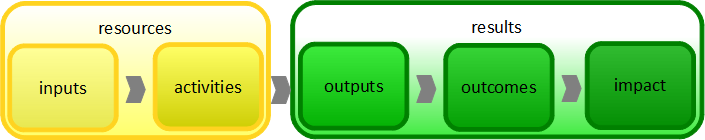

RBM is also critical of many donors’ focus on inputs (funds and resources) and activities, and promotes a shift towards the results of the project: its tangible outputs, its effects and its impact. That is the ‘Results’ part of RBM. As for the ‘Management’ aspect, RBM provides a number of tools to monitor the performance of your project. Are you getting the results you wanted? How can you be sure? How many resources do you use? These are the questions to which RBM can give an answer

Compared to its predecessors, RBM also takes more into account that the context or environment in which you’re working is dynamic and influences your project – in positive ways but also in negative ways. RBM stimulates you to think about assumptions and risks, not just at project design time, but over the whole course of your project.

RBM also tries to step away from the top-down or project manager’s view of PCM. It takes a step further than the classic idea of participation that limits itself to questioning the beneficiaries or stakeholders in order to determine the project’s objectives and other elements necessary for the design of the project. In RBM, partners and beneficiaries share the responsibility of making the project a success together with the lead NGO.

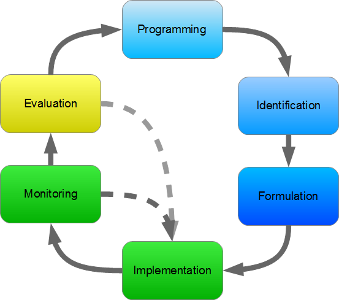

Results Based Management also uses the idea of the learning cycle: learning from practice (past projects) using the information gathered from the different monitoring and management tools and from evaluations and analyses to develop new strategies and new projects.

Basic concepts of Results Based Management

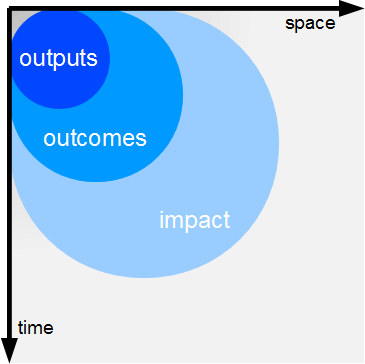

Not surprisingly, the ‘Result’ is the central concept of Results Based Management. Results are describable or measurable changes resulting from a cause and effect chain. This results chain describes how you will go from the current situation to the desired situation. In RBM, there are three types of results:

- Direct results or outputs, which are produced by the project’s activities, using the project’s resources. These are the things that normally are under our control.

- Intermediate results or effects, which are the consequences of the direct results. Often it takes a while for these effects to materialise. They are not completely under our control, very often there may be other influences at play here. Effects can be expected (as described in the project’s logframe), but also unexpected because of the very fact that there may be other influences at play. Effects can be positive, but our outputs may also lead to some negative effects.

- Final results or the impact of our project. Generally the impact is only visible after a longer period and in the broader environment (not just with the people that were directly involved in the project). Like effects, the impact can have expected or unexpected elements that can be either positive or negative.

According to the Canadian International Development Agency, which pioneered the use of RBM in international development, Results-based management is a life-cycle approach to management that integrates strategy, people, resources, processes, and measurements to improve decision making, transparency, and accountability. The approach focuses on achieving outcomes, implementing performance measurement, learning, and adapting, as well as reporting performance.

RBM is:

- Defining realistic expected results based on appropriate analysis;

- Clearly identifying program beneficiaries and designing programs to meet their needs;

- Monitoring progress toward results and resources consumed with the use of appropriate indicators;

- Identifying and managing risk while bearing in mind the expected results and necessary resources;

- Increasing knowledge by learning lessons and integrating them into decisions; and

- Reporting on the results achieved and resources involved.

Main principles of RBM

The RBM approach is based on six main principles:

- Simplicity: RBM tries to identify a strategy that is easy to understand and easy to put into practice. RBM provides a number of simple tools to help with project design, project management and achieving the project’s results.

- Action learning: RBM integrates the learning cycle. We learn by doing and what we learn enables us to strengthen our capacities, improve the quality of our projects and get better results. This learning cycle is inclusive: it’s not just about the leading NGO that learns and improves, but everyone involved in the project. Partners and beneficiaries are empowered through learning and participation, and gradually see how important their role is and as a consequence they take up more responsibility.

- A flexible method: RBM adapts itself to different contexts and different types of projects. It’s even possible to introduce RBM into projects that are already running.

- Partnership: participation of partners and stakeholders is not only important during the formulation of the project, but also during the execution, monitoring and evaluation (appreciation) of the project. This is the only way to come to solid project design with relevant objectives AND to durable results and a sense of ownership of those results from the part of the local population and partners.

- Accountability, or sharing responsibilities between the partners. In RBM, participative decision making is important, as well as clearly defining each party’s responsibilities and tasks.

- Transparency: using well designed and well-chosen indicators, it must be possible to give a clear image of what the project is doing and where it is going. Transparency towards the donors, but also transparency towards the partners and beneficiaries. RBM introduces the Performance Framework to clearly identify objectives, how their progress will be measured (and at what frequency), who will be responsible for what, etc.

RBM step by step

RBM pr ovides an approach and tools for both project design and project execution. Furthermore, it also uses the concept of the learning cycle to learn from one project and use it for future activities. We’ll describe the RBM process in 13 steps (for good luck).

ovides an approach and tools for both project design and project execution. Furthermore, it also uses the concept of the learning cycle to learn from one project and use it for future activities. We’ll describe the RBM process in 13 steps (for good luck).

- Project design

- Identification and planning

- Step 1: Stakeholder analysis and identification of beneficiaries

- Step 2: Identification of problems and needs

- Step 3: Determining the Performance Framework (PF)

- Step 4: Finding indicators and developing the Performance Measurement Framework

- Step 5: Identifying assumptions and analysing risk factors

- Step 6: Activities, resources and responsibilities

- Deciding on the intervention logic (project logic)

- Step 7: Developing the logical framework

- Step 8: Writing the project proposal

- Identification and planning

- Project execution

- Learning (step 13)

Project design

The project design phase has two main parts:

- Identification and planning with the stakeholders and beneficiaries

- Deciding on the intervention logic and developing the logical framework and the project documentation

Identification and planning

During this first phase, problems and issues are identified, as well as possible ways to tackle them (strategies for solutions). Then the best intervention strategy is selected, which will be the basis for the project plan.

Usually the organisation that takes the initiative will have a basic idea of the problem it wants to tackle, the future intervention area and possible stakeholders. In this phase, these preliminary ideas are put to the test through participatory methods. But first you need to find people that want to help you with the identification of the problems and needs.

Step 1: Stakeholder analysis and identification of beneficiaries

There are different categories of stakeholders that you could involve in the project’s design. In first instance, the potential beneficiaries of course: these can be local farmers or entrepreneurs; people that make use of medical facilities; villagers; local business people; women; young people; members of minority groups… It all depends on the type of project and the local situation. In addition, you can talk with local authorities, local NGOs, village councils (village elders), ministry delegates and so on.

For each group you can describe:

- To what categories they belong

- What their number is

- What their socio-economic situation is and any other relevant characteristics

- What their potential is to contribute to a solution for the selected problem(s)

Step 2: Identification of problems and needs

During this step, a problematic situation is analysed with the different stakeholders, including the (potential) beneficiaries of the project. Usually a method like the problem tree analysis or a fishbone analysis is used. Once the central problem is identified, the participants to the workshop can identify its root-causes. The following step is to describe the negative consequences of the problem and select the most important ones.

During this step, a problematic situation is analysed with the different stakeholders, including the (potential) beneficiaries of the project. Usually a method like the problem tree analysis or a fishbone analysis is used. Once the central problem is identified, the participants to the workshop can identify its root-causes. The following step is to describe the negative consequences of the problem and select the most important ones.

The problem tree then can be turned into a solutions tree, which will probably contain different ways of approaching the problem. Depending on the possibilities and capacities of the different partners and of the beneficiaries, the best approach or strategy to dealing with the central problem can be identified.

Step 3: Determining the Performance Framework (PF)

The Performance Framework (not to be confused with the Performance Measurement Framework) describes the intervention logic of the project. It describes how what we invest and what we do will lead to tangible results.

The Performance Framework (not to be confused with the Performance Measurement Framework) describes the intervention logic of the project. It describes how what we invest and what we do will lead to tangible results.

With the information from the solution tree analysis (or another method), the basic elements of the project can be identified:

- What is the purpose of the project (the central problem in the problem/solution tree analysis)?

- What results do we expect?

- Who will benefit from the project?

- What is the best approach (strategy)?

The next step is to determine the results chain:

Outputs, effects and impact have to be described in such a way that they are clear for everyone and can’t be misinterpreted. It’s best to avoid overly complex formulations and complex concepts that may be interpreted differently in various contexts (for instance: ‘gender equality’ or ‘durability’). It’s better to explain what you mean by those fancy concepts in as plain a language as possible.

The performance Framework will later be used to fill out the left column of the logical framework.

Step 4: Finding indicators and developing the Performance Measurement Framework

The Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) is the next step after the Performance Framework. For each result that we expect for our project, we’ll identify indicators, ways to verify the information, ways to collect the information, the frequency at which the information is gathered and who is responsible for gathering that information.

Indicators

For each level in the results chain (outputs – effects – impact), indicators have to be found. ‘Indicators’ does not necessarily equal ‘hard numbers’. However for RBM it is important to find indicators that are clear, concise and not up for interpretation. It’s a good idea to list as many indicators as you can to start with, and then select the most pertinent ones. You want these indicators to be:

- Valid: this means that the indicator measures the result

- Sensitive: when the result changes, does the indicator change with it?

- Reliable: does the indicator give the same value over time or when observed by different observers?

- Simple: how difficult is it to gather data and to process it?

- Usable: can we use that information to take decisions and to learn?

- Affordable: do we have the resources to gather the information?

Finding indicators is again a participatory exercise. At the very least people have to be able to be feedback to the indicators you suggest. It’s a good idea to test your draft list of indicators in real-world conditions.

Outreach indicators

Apart from the ‘classic’ output, effect and impact indicators, RBM also uses outreach indicators. Outreach indicators say something about the people that you reach. Very often, project indicators only talk about things like production, quality improvement, availability of services, training and capacities, etc. The human dimension – in other words the very reason for doing a development project in the first place – is totally left out.

RBM pushes you to reflect about outreach on all three levels of the results chain. The higher up the chain, the more difficult it becomes to accurately assess how many people the project will reach. Here are some questions to help you identify the outreach:

- Who are the direct and indirect beneficiaries at each level of the results chain?

- How many people will (ultimately) benefit from the project? How many men and how many women will benefit? What age groups will benefit? How many people from rural or urban areas will be involved?

- What are the main characteristics of these people? What is their social, economic, cultural… situation. What is their health situation? How well are they educated? Are their rights respected? Do they live in fear of violence or conflict? And so on…

- What will the project do for these groups? What will the positive and negative results be?

Verification sources

Where can you find the information for your indicators? You can make use of:

- direct observation

- information from various official reports and statistics

- interviews

- pictures

- satellite images

- …

In some cases it may be interesting to have various sources of information that you can compare to each other (triangulation). Or you may need to combine different sources of information to get a complete picture.

Another question is how you will practically gather the information: using registration forms or questionnaires; registering it in a database or a spreadsheet; doing surveys… You must also decide on how regularly you will gather the information. And last but not least whose responsibility it is to gather what information.

Who is responsible for what?

There is more than just deciding on who is responsible for gathering certain pieces of information. It has to be clearly established how the responsibility for achieving the results is shared.

- Who is responsible for what activities and for what tangible outputs?

- How will the resources be distributed and who will manage what resources?

- How will the partners contribute to the project in terms of human resources, funding, time

- etc.

The Performance Measurement Framework (PMF)

With all this information, the PMF can be established:

|

|

Indicators |

Verification sources |

Collection method |

Frequency |

Responsible |

|

Impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Effects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outputs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Activities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outreach |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inputs |

|

|

|

|

|

The outputs and activities matrix

The O&A matrix is a planning tool that can be used to elaborate the more practical side of the project. For each output and effect it allows you to specify what activities are necessary, what resources (inputs) you will need and who will be responsible for that activity.

|

|

Activities |

Resources |

Responsible party |

|

Effect 1 |

|

|

|

|

Effect 2 |

|

|

|

|

Output 1 |

|

|

|

|

Output 2 |

|

|

|

Step 5: Identifying assumptions and analysing risk factors

When you take a closer look at the results chain, you will probably see that the cause and effect relations between activities and outputs, between outputs and effects and between outputs and impact are conditional. Basically, if all holds well we can expect that we’ll get the results that we want at the end. This means that we (implicitly) make a number of assumptions. What does it mean ‘if all goes well’?

RBM makes a distinction between assumptions, which are positive conditions, and risks that are negative factors. Both assumptions and risks can be internal or external factors. Internal factors are the things we have under control: the capacities of our staff, our management capacity, delegation of authority, etc. External factors are influences from the environment on our project.

There are different types of risks and assumptions:

- Operational risks are linked to the activities, the availability of resources, logistical problems, etc.

- Objectives risks and assumptions have a direct influence on whether we will be able to achieve our results.

- Financial risks

- Reputation risks

Risks can have varying degrees of impact on our project. The influence of some risks will be negligible, or else they may be a nuisance but nothing we can’t handle. In other cases they may have a severe influence on whether we will be able to realise our objectives. In the worst case scenario, we may be forced to stop the project altogether.

Another factor we have to assess is what the chance is realistically that a risk will materialise during the project. The combination of the impact that a risk might have and its likelihood helps us to assess the situation and take (preventive) action. If a risk has low impact and is not likely, it’s really not worth mentioning in your logframe. High impact risks with low likelihood still have to be monitored. And when a risk really threatens the project and is very likely, it’s probably not worth starting the project in the first place.

Merely identifying the risks is not enough: it’s also important to reflect on what you will do if or when the risk occurs:

- Are you going to try to avoid the consequences or the risk altogether (for instance through disaster risk reduction)?

- Are you able to deal with the consequences?

- Will you be able to transfer the burden to someone else (an insurance company for instance)?

- Or will you do your best to mitigate the consequence as much as possible?

The Risk Register

The Risk Register is a tool to identify and monitor risks over the course of the project. It resembles the PMF and lists the risks, the risk indicators, information sources, methods to collect information, the frequency at which the information will be collected and who is responsible for this information gathering.

|

Risks |

Indicators |

Information sources |

Data collection methods |

Frequency |

Responsible party |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 6: Activities, resources and responsibilities

At this point, it is time to take a look at the activities from a very practical point of view:

- When will the activity start and how long will it take? Does the activity follow another one? Does it depend on that previous activity (does it need the outputs of that previous activity as inputs)?

- What inputs (resources) are needed: people, knowledge/information, money, equipment and tools, natural resources, energy, space, logistics…

- How much preparation time is needed? Who is involved in preparation?

- If the activity is complex, a specific budget may have to be made up.

- Who is involved? Who is responsible for managing the activity? Who will execute the activity (one of the partners, or maybe a subcontractor or service provider)? Who can give support? Who has to be consulted beforehand (authorities, beneficiaries, management…)? Who needs to be informed? This series of questions is called RASCI, short for Responsible, Action, Support, Consulted, Informed (although other flavours also exist, such as RACI or RASI).

- What methods or procedures have to be followed?

- What tangible outputs are expected (reports, goods, trained people….)?

- Does the activity have to be repeated over time? How many times/how regular?

- How will the follow-up be organised? How much follow-up time is needed? Who is responsible for follow-up?

For simple activities, you may not have to go through this whole list of questions, but complex activities need to be planned and budgeted in some detail.

Deciding on the intervention logic (project logic)

The intervention logic is the cause-and-effect chain or results chain that’s been identified in the Performance Framework:

- You gather the necessary resources (human resources, materials, equipment) and funds

- With the resources, you can organise the activities

- The activities produce outputs: goods, services, knowledge, information, etc. These are the immediate results.

- When these outputs are used, they lead to effects or intermediate results.

- The effects contribute to the final results, or impact.

This information is presented in the logical framework (first column, except for the resources).

Note that compared to the ‘classic’ logical framework as it is used in LFA and PCM, there is a dimension of time in the intervention logic of RBM, as well as a spatial dimension. We immediately get the outputs as a consequence of the activities. But it takes time for the effects to materialise (near the end of the project or maybe even after it) and the impact will only be visible after a long time (sometimes years or even decades after the project). The outputs will be used directly by the people involved in the project, while the effects are generally felt by those people and their immediate surroundings (family, clan, village). The impact on the other hand may be visible in a widespread area (region, country, internationally).

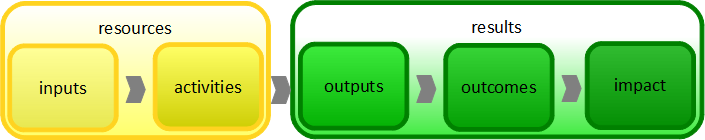

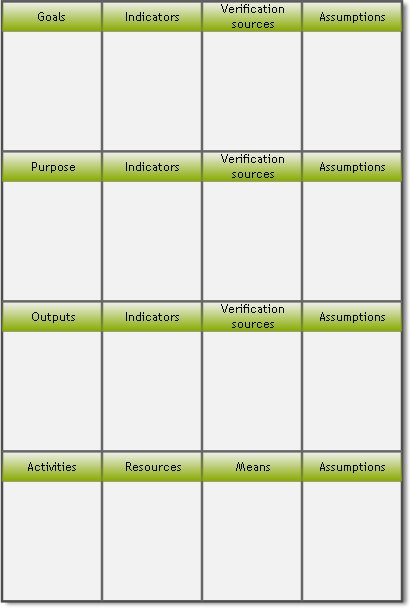

Step 7: Developing the logical framework

Now it’s time to bring together all the information that you’ve gathered so far into the logical framework matrix:

- The first (left) column contains the intervention logic.

- The second column contains the indicators

- The third column contains the verification sources

- The fourth column contains the assumptions/risks.

Once you’ve filled out the basic ideas, it’s time to worry about formulation. Make sure that your results are clear and not too overly complex. It’s important that they are unambiguous – meaning that they are understood the same way by everyone involved in the project. Avoid overly complex concepts such as ‘gender neutral’, ‘globalisation’, ‘sustainable’ that can be interpreted in many different ways. If you need such concepts, make sure that you specify them in your logframe and/or explain them somewhere.

It’s best to make sure that your results are formulated in a SMART way:

- Specific: What exactly will change? Where? For whom (who will benefit)?

- Measurable: How much will it change? You have to set a target.

- Attainable: make sure that you don’t make unrealistic expectations about the change that you can achieve through your actions.

- Realistic, in the sense of based on a real world situation: make sure that what you propose is coherent and pertinent for the problems that your beneficiaries face.

- Time specific: indicate the timeframe in which the change will take place. Outputs have to be realised within the timeframe of the project. Effects may occur near the end or right after the end of the project. Impact is generally only visible well after the project.

Outputs can be things or services, but at least on the level of the intermediate results (the purpose of your project or the specific objective in PCM/LFA talk) talk about results in terms of people. You are trying to improve the lives of your beneficiaries (clients), not some kind of abstract change of situation.

Step 8: Writing the project proposal

The logical framework and the other tools such as the budget, the PMF and the risk register provide you with the basic information for the project proposal document. Generally, the narrative project document contains information about:

- Introduction of the organisation

- Identification

- History

- (Strategic) objectives of the organisation

- Summary of the project

- Detailed description of the project:

- Title and location

- What the situation is of the target groups in the area of intervention/country;

- Who the partners are;

- What the objectives are;

- Description of how the objectives, target groups and partners were identified (explaining this was done one a participatory basis).

- How the objectives fit in the donor’s policy/the country development strategy;

- What activities will be executed;

- What resources are needed (overview of main costs, with detailed budget in annex)

- How the activities and results will be monitored and evaluated

- What the risks are and how they will be dealt with;

- How the partners will collaborate with local authorities and other stakeholders

This narrative project document is completed with a number of annexes:

- The budget proposal, detailing every expense and sometimes regrouping them per activity or output

- The logical framework of the project

- A detailed planning of the activities

- Other documents to explain how the organisation manages its projects, such as partner identification forms, registration forms for beneficiaries and target groups, the official NGO registration and so on.

In the concept of RBM, the partners should be closely involved in the elaboration of the project proposal. This means that they participate in the writing but also that they officially approve the end result. Following this process of internal review and approval, the proposal is sent to one or more donors.

Project execution

RBM doesn’t end with project design. The systems for monitoring and evaluation of performance and for risk management that were designed during the design phase have to be deployed during the initial stages of the project. In addition, RBM provides you with a set of tools that you can use for project management, follow-up and evaluation.

Monitoring and evaluation of performance

Performance is an important concept in RBM. It means the progress towards the different results. This means that monitoring isn’t restricted to verifying whether the activities take place according to planning. The plan may have to be modified, but the most important thing is to know whether the results are or will be achieved (in time). The idea behind tracking the performance through monitoring and evaluation, is to better manage the outputs and effects that are the real development results.

Compared to other approaches, RBM puts the emphasis on the effects or intermediate results (purpose of the project), instead of on the immediate results or outputs (or even activities).

However when you develop your monitoring system, in the RBM approach it is important to work on a participatory basis. In order to avoid that you develop a system that is too complex and cumbersome, you need to make sure that the monitoring system:

- Does not weigh too heavily on the available resources

- Does not take too much time and effort (or else people will skip monitoring and reporting altogether)

- Involves as many people as possible, not only the beneficiaries but also other stakeholders to get an external view and verify (triangulate) information

- Doesn’t use too many indicators and different sources of information (or sources that are very complex to gather). Also remember that basic statistics that are readily available in developed countries are often not available (or outdated, or unreliable) in developing countries.

The information from the monitoring system should allow you to act: to modify your planning, your activities, the distribution of resources, etc. to changes in the context and to make sure that the results will be achieved.

Similarly, the evaluation of the project’s effects should be done based on participation of the stakeholders. Any evaluator (of the organisation or external) should consult the stakeholders, including the (intended) beneficiaries of the project.

Step 9: Collecting information on performance

The monitoring system with its indicators and description of who will measure what at which intervals (or for how long) allows you to collect information in a systematic way. Once collected, the information can be aggregated and synthesised if necessary and then be analysed.

Information gathering happens at regular intervals (daily, weekly, monthly, every 3 or 6 months or sometimes once a year) or every time an activity occurs. Sometimes this happens by going over the whole list of indicators and establishing the situation for every indicator at that moment, for instance during a monitoring mission. In this case you will get a set of information (data) at a given point in time. By putting this information in a table and adding new columns for consecutive sets, you will be able to see the evolution.

In other cases information gathering for different indicators happens at different moments and you don’t measure the whole set of indicators each time.

Step 10: Analysing the project’s performance

Using the Performance Measurement Framework, you can analyse the information that you gathered to assess:

- Whether the activities and the use of resources lead to the desired results. The relation between the use of resources and the results allows you to appreciate the efficiency of the project.

- Whether the outputs lead to the desired effects or the realisation of the purpose of the project. In other word, is the project effective?

- Does the intervention strategy that’s been selected lead to the desired direct and intermediate results. This is about the pertinence of the project.

- Does the institutional, political, social and organisational environment of the project enable its success? Or is it slowing down the project or preventing the achievement of certain elements? We’ll go deeper into this question under risk management.

Step 11: Reporting

Analyses and the conclusions are generally noted down and distributed in the form of reports. Again, keeping the participatory nature of RBM in mind, you should not forget that reporting is not something you do for the benefit of the donor and for headquarters only (upward accountability). Partners and beneficiaries must be informed too (downward accountability). The whole idea of this participatory approach to monitoring and learning is to stimulate a feeling of ownership of the project and its results by the beneficiaries.

Normally, a series of intermediate progress reports are produced over the course of a project. Often donors or organisations will have their own templates that are mandatory to use. In any case, such reports should contain:

- An overview of the project’s realisations so far

- An overview and analysis of the things that have yet to be realised

- A description of what will be done in the coming period to reach the objectives

- A brief description of the evolution of the general situation (project’s environment)

- A status update about the resources: financial expenditure, human resources, logistics, planned missions…

- A financial planning for the coming period

Step 12: Follow-up of risks and assumptions

During the project’s design phase, the risks and assumptions were identified and listed in the risk register. This risk register can be used during the execution of the project to reassess the situation and the risks periodically.

The risk register allows you to reassess whether:

- The likelihood that the risk will occur has changed

- The potential impact of the risk on the realisation of the project’s objectives has changed.

- There are any new risks that can be identified and that require monitoring in the future

It is possible that the project becomes less sensitive to certain risks over time, because the population becomes more resilient to those risks thanks to the achievements of the project. On the other hand, new and unexpected risks may materialise. This may even lead to a situation where it becomes practically impossible or too dangerous to continue the project. In such extreme cases, the information gathered using the risk register may help you support your decisions and convince your donor.

Step 13: Learning

Like Project Cycle Management, RBM is based on the idea of the learning cycle. In fact, you could say that there are two learning cycles. The first one is a cycle that includes the activities, the monitoring and the evaluation. By tracking the performance of the project, you are able to learn what you need to modify the execution of your project in a flexible way. This learning ensures that you achieve your final objectives.

The second cycle gathers the experiences from one project and uses them for consecutive projects. The information gathered from (monitoring) reports and evaluations is used to modify the organisation’s strategy, to plan new projects and to improve the overall approaches of the organisation. This is where Results Based Management meets organisational learning.

RBM is good for you – or is it?

A big advantage of Results Based Management as compared to other logframe methods is that it tends to be less top-down. RBM puts a lot of emphasis on participation, not just during project design (like PCM and LFA) but also during the execution of the project (including monitoring). At the same time, this is exactly what makes this approach a bit unwieldy. All this participation is fine for creating feelings of ownership and making sure your objectives are relevant, but it also takes time and effort. As a consequence, RBM is easier to handle for big organisations than for smaller ones.

But even small organisations can benefit from the many practical tools that RBM provides. This approach provides you with a clear and detailed way of designing and executing your project. Although it takes time to go through the step-by-step instructions, they do lead to a well-designed project with clear and relevant objectives. The notion of ‘performance’ has the additional benefit that the link between the resources (funding) that you use and the results that you get is clear. This is one reason why RBM is favoured by donors.

The risk management tools included in RBM help you to do something concrete with the often neglected fourth column of the logframe. Instead of just imagining what could possibly go wrong (‘we run out of money!’), this method allows you to identify real risks and assess what could be the effect should they materialise.

However, RBM does suffer from the same problems as its cousins, LFA and PCM. It is based on a linear cause-and-effect concept that tends to simplify what are often very complex realities. RBM may force you to identify cause-and-effect relations where there are none (or they may be questionable). It doesn’t take into account that you may not be the only organisation in the vicinity that has an influence on this problem.

And then there is the question of RBM-as-it-is-meant-to-be versus RBM-as-it-is-pushed-by-donors (and big organisations). The participatory design process may lead to a project proposal that is well founded, but once a contract with a donor is signed, it is cast in concrete. Away are the flexibility, the learning cycle and the possibility to adapt your activities according to what you measure and learn. Upward accountability becomes all important and sharing information with beneficiaries, partners and other stakeholders comes in second place – or in third place, or fourth, or… And the focus may shift again from achieving the intermediate results (purpose of the project) to financial management and executing the activities as planned. But these problems are not inherent to the approach itself, but to the way it is used or to how organisations are forced to use it.