Project cycle management (PCM)

Project Cycle Management or PCM is an approach that allows you to manage many different projects and improve the quality of your projects over time. PCM uses the idea of a continuous learning cycle and incorporates logical framework analysis to guarantee that the beneficiaries are involved in the project's design. However, PCM's built-in flexibility is often threatened by the way its tools and models are used in a rigid way by donors and strong NGO partners.

PCM or Project Cycle Management is an approach to manage multiple projects or programmes and to improve the quality of projects by learning from one project and applying the lessons in the following ones. The approach was introduced by the World Bank in the 1980, and spread throughout the development world in the 90s, when it was picked up by the European Commission. Following an evaluation on Aid Efficiency, the EC introduced PCM as its main approach to manage and evaluate development project proposals.

Since then, other donor agencies and NGOs picked it up, although not always voluntarily. The fact that donor agencies actively pushed PCM and models and tools related to PCM led to resistance and often gave this approach a bad rep. One of the main tools of PCM, apart from the overall cycle, is the logical framework. With its emphasis on participation from both partners and beneficiaries, PCM incorporated the logical framework approach (LFA) and added two main elements:

- The link between the long term policies or the strategic framework of the organisation and their execution in the form of projects (or programmes)

- Learning from experiences: PCM puts a heavy emphasis on monitoring and evaluation. The main idea behind the cycle is that the quality of projects gradually improves as lessons are passed on from one project to the next. Also, within a single project there is flexibility and learning, as continuous monitoring allows the people who manage the project to adapt the activities and planning to the (changing) situation in the field. At least, that is the theory.

Another benefit of PCM, both from the management point of view and the quality improvement point of view, is that it presents a standardised approach with standardised tools. However, this is also the main reason why PCM meets with a lot of resistance. As a project management approach, PCM is mainly interesting for donor agencies and large NGOs. The problem is that these large organisations tend to force their partners to use the procedures and tools in a very rigid way. This goes up to the point that the emphasis shifts from flexibility in the field and learning between projects, towards respecting contracts, forms, procedures, administrative rules, budget restrictions, and so on. PCM is used to manage contracts, control projects and see to it that laws, regulations and budgetary restrictions are respected. Often, this leads to a situation where both beneficiaries and the NGO or NGOs that manage the projects are bound by hands and feet to the contract, the logframe, the budget and the planning. This is a far cry from the original notion of flexibility and learning.

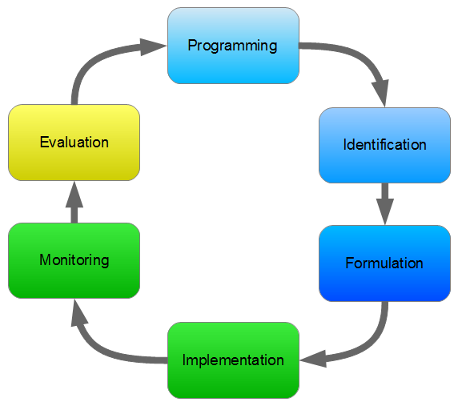

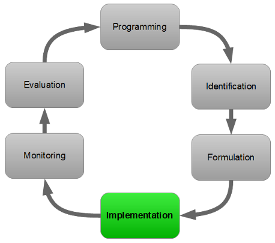

The Project Cycle

In its basic form, the Project Cycle counts six phases. However, as some donor agencies, NGOs and consulting firms tend to bring out their own versions, this number of phases and their content may vary.

The phases are:

Often, implementation and monitoring are combined in one step. Some donor agencies add an additional step of ‘Financing’ or ‘Approval of the proposal’ between ‘Formulation’ and ‘Implementation’. From the point of view of the NGOs that want to introduce a project, negotiating or lobbying is another step that could be added between programming and identification or between identification and formulation.

The first three steps can be seen as the design phase of the project. This can easily take up to two years before the final approval is given and work (or practical preparations) can begin. The duration of the project itself depends on its activities and the needs of the beneficiaries, but more often than not also on budgetary restraints or the regulatory framework of the donor. That is why consecutive projects (sometimes called actions) are combined into a larger programme. Again, in such a programme it is important to learn from previous actions, but in reality this may not always be the case (or only to a limited extent).

Programming

The programming phase establishes the link between the individual project and the overall strategy of the organisation. How does the NGO or development actor want to realise the main purpose of the organisation (as expressed in its vision and mission for instance) over the next couple of years? To answer this question, many organisations go through a participatory process with their beneficiaries and with other stakeholders. This often leads to some kind of long term strategy document, that contains general orientations about what activities and projects the organisation will do, in which countries or regions, with what target groups and counting on what means (own resources, donor funding, etc.)

The programming phase establishes the link between the individual project and the overall strategy of the organisation. How does the NGO or development actor want to realise the main purpose of the organisation (as expressed in its vision and mission for instance) over the next couple of years? To answer this question, many organisations go through a participatory process with their beneficiaries and with other stakeholders. This often leads to some kind of long term strategy document, that contains general orientations about what activities and projects the organisation will do, in which countries or regions, with what target groups and counting on what means (own resources, donor funding, etc.)

Some organisations limit this reflection to their activities in the field. Other take a step further and develop a long term vision for all aspects of their work: human resources management, financial management, quality management, external communications strategy, lobbying strategy and so on.

Often, the organisation’s strategy will fit into a broader vision, for instance common policies developed with the NGO sector in your country. This may also lead to specific thematic or country policies that are added to the overall strategy and that explain how the organisation will implement these policies over the next couple of years (for instance a gender strategy, a food security strategy, a country strategy, an ecological durability strategy, etc.)

At this step, the organisation may also develop common tools or approaches that will be used in the coming years. These may include practical guidelines that can be used for the different projects, or lists with criteria (for instance for the selection of partner organisations or beneficiaries) and other tools.

All this doesn’t come out of the blue. The idea behind the project cycle is that these reflections are fed by the lessons learned from previous projects, amongst other things through evaluations but also by asking those who were involved to participate in this phase.

Identification

In this step, the idea for the project is initiated and the organisation verifies whether this idea really responds to the needs of the (future) beneficiaries. In other words, the pertinence of the project is checked. This means that we have to see if it fits our strategy on the one hand. But more importantly it has to be based on a thorough knowledge and analysis of the situation in the target zone/country and of the needs of the beneficiaries. This is where the expertise of the local partners comes in – generally to guarantee the quality of the project, it is expected that the project is formulated together with the local partners.

In this step, the idea for the project is initiated and the organisation verifies whether this idea really responds to the needs of the (future) beneficiaries. In other words, the pertinence of the project is checked. This means that we have to see if it fits our strategy on the one hand. But more importantly it has to be based on a thorough knowledge and analysis of the situation in the target zone/country and of the needs of the beneficiaries. This is where the expertise of the local partners comes in – generally to guarantee the quality of the project, it is expected that the project is formulated together with the local partners.

As a result of this phase, an initial draft of the project is elaborated which contains all elements of the intervention logic:

- What activities do we want to do?

- To achieve what tangible results (outputs)?

- To remedy what situation? Why do we do this project? In other words what is the purpose of our project?

- How will our project contribute to improving the overall situation in the intervention area? What will the impact be in the long run?

In other words, the first column of the logical framework is elaborated. In PCM – as in the logical framework approach – the idea is that there is a cause-and-result chain. The activities lead to the tangible outputs, and through the combination of these outputs we will realise the purpose of our project.

At this stage, we also have a look at the resources we will need and try to estimate what the overall budget of the project will be.

Often this project draft must go through an approval procedure within the organisation, meaning that the director, the executive board or some form of a project committee will have to scrutinise the project and give their approval.

Formulation

Once the basic concept of the project is determined and approved, it is time to go into detail. Often, this comes down to writing a detailed project proposal. In the concept of PCM, models are used for establishing:

Once the basic concept of the project is determined and approved, it is time to go into detail. Often, this comes down to writing a detailed project proposal. In the concept of PCM, models are used for establishing:

- The narrative proposal, which gives an overview of the project and explains in detail:

- What the situation is of the target groups in the area of intervention/country;

- Who the partners are;

- What the objectives are;

- How the objectives fit in the donor’s policy/the country development strategy;

- What activities will be executed;

- What the risks are and how they will be dealt with;

- How the partners will collaborate with local authorities and other stakeholders

- The budget proposal, detailing every expense and sometimes regrouping them per activity or output

- The logical framework of the project

- A detailed planning of the activities

- Other documents to explain how the organisation manages its projects, such as partner identification forms, registration forms for beneficiaries and target groups, the official NGO registration and so on.

Sometimes the NGO has (and is allowed to use) its own models, but often donor agencies will oblige NGOs to use their templates.

Often these templates help the organisation to really think the whole project through and to conceive of every detail. On the other hand, the amount of detail that is sometimes requested can be overwhelming and very often the same information has to be repeated over and over again between projects – which again goes against the idea of continuity and learning. But with all this information, the partner organisations will get a good idea of the viability of the project and any pitfalls that may be on the road.

It is at this stage that we can integrate the whole logical framework approach as a participatory approach to determine the various elements of the project:

- Validating and detailing every element of the intervention logic (first column of the logframe)

- Thinking about how the project will be monitored and evaluated (second and third columns of the logframe).

- Reflecting about risks and assumptions (fourth column), and how to deal with problems should they occur (and what their possible impact will be).

- Practical organisation like who does what and when? How will the communication and reporting be organised? Who is responsible for what?

Implementation

Once funding is secured, there is nothing to stop us from executing the project (although ‘nothing’ may be too optimistic sometimes). At this step, we can start with the practical preparations of our project: recruiting additional staff; organising the project team at different levels and locations; setting up logistics and purchasing new equipment; introducing ourselves and the project to the people, the media, the local authorities, the representatives of international organisations and so on.

Once funding is secured, there is nothing to stop us from executing the project (although ‘nothing’ may be too optimistic sometimes). At this step, we can start with the practical preparations of our project: recruiting additional staff; organising the project team at different levels and locations; setting up logistics and purchasing new equipment; introducing ourselves and the project to the people, the media, the local authorities, the representatives of international organisations and so on.

The monitoring and accountability system has to be put in place too. This includes the system for financial management and reporting; the system to monitor the execution and results of our activities; the administrative management system; the risk monitoring system and emergency handling system; and the planning of financial audits and (external evaluations).

At this point in time, the situation of the beneficiaries is measured before the activities start, using the indicators. This is known as the baseline, which will serve to compare the evolution of the situation of the beneficiaries to as the project progresses. However, some donors will oblige you to establish a baseline during the formulation phase and incorporate it in the project proposal. Even so, it may be a good idea to establish the situation at the very start of the project, especially when it’s been a while since the baseline was established, because other things may have influenced the beneficiaries’ situation.

The project’s planning that was established during the formulation phase may also need to be updated. It is not rare that a lot of time has passed between the development of this planning and the final approval of the project by the donor. In the meantime the situation may have drastically changed. Experience also shows that it is only now that serious reflection is given to the planning of the activities, as the project team is confronted with the reality and limitations of working in a given setting with certain resources and time available.

Implementation is all about doing the right activities to respond to the actual needs of the beneficiaries. The information you receive from your monitoring system should allow you to respond flexibly to those needs. At least that is the original idea behind the project cycle. In the worst case, you are totally bound by your contract with the donor and obliged to follow it to the letter, even if you know that the situation has changed and that you are not doing the right things. Most donors are open to adapting the original contract in some way, but often within limits. Also, the procedure to change your contract may be cumbersome and slow, and modifying the contract is not something you would go through more than once during the project.

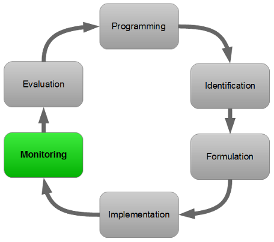

Monitoring

The monitoring and implementation phases are often taken as one because they are so intertwined. In any case it is clear you can’t speak of consecutive phases because they go together. Monitoring is about checking whether your project is going as planned, meaning that:

The monitoring and implementation phases are often taken as one because they are so intertwined. In any case it is clear you can’t speak of consecutive phases because they go together. Monitoring is about checking whether your project is going as planned, meaning that:

- You’re doing the activities according to plan

- You’re getting the outputs that you want

- You’re spending the budget according to plan

Monitoring is not about the fundamentals of your project, i.e. the question whether you’re doing the right things in the first place.

To monitor the project’s outputs, you’re using the indicators of the logframe. To monitor the progress of the activities, you’re using the project’s planning (updated). To monitor expenses, you’re using the project’s accountancy and compare it with the budget.

In the concept of PCM, monitoring is needed to adapt your project flexibly to the ever changing needs and the ever evolving situation in the field. Monitoring should allow you to take project management decisions on the go:

- Change the activities that you do, or change the order of the activities, or put an end to certain activities because they don’t lead to the results that you expected.

- Verify whether outputs are achieved in time, and change priorities and/or reroute resources (staff, finances, equipment…) to make sure they will be achieved.

- Avoid financial mismanagement, or expending too much or too fast. Maybe the cost of certain activities may have to be reviewed and other solutions may have to be found. In other cases the costs will turn out to be lower than expected, and additional activities may be organised to exceed the original objectives of the project.

- Determine whether you should start up a procedure to re-negotiate parts of your contract: because the situation has changed drastically; because risks have materialised and you can’t handle them as you’d hoped; because you’re spending more than expected; because you want to re-allocate your resources; etc.

In this sense, monitoring does not equal controlling. However, in practice the opposite is often true and monitoring becomes something to satisfy the donor and produce the necessary reports in time.

In any case, the information you get from your monitoring system is not only used to manage the project, but also for accountability. There are two kinds of accountability:

- Downward accountability: you use the information from your monitoring system to show the beneficiaries what they’ve achieved so far and how they and their situation have progressed since the beginning of the project. This is also an element of participation and it is important to create ownership of the project and of its results.

- Upward accountability: the information from the monitoring system is used to report to the partners, to ‘headquarters’ and to the donors.

Again in reality, downward accountability is often forgotten, and the emphasis is on reporting to the donor. A lot of time can go into reporting, also because information has to be poured into the formats provided by the donor. This is especially true for financial reporting: an inordinate amount of time can be spent on making sure all tickets and invoices are there and eligible according to the donor; classified and registered in the accountancy system; verified and verified again; audited internally and externally…

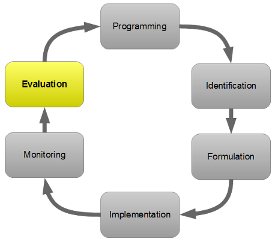

Evaluation

While monitoring is about checking whether the project is executed according to plan, evaluation is about the very reasons why you’ve developed your project in the first place. Do the results of your project effectively lead to the desired change in the lives of your beneficiaries? Was your intervention strategy effective? What are the expected and unexpected effects and impact of your project? What can you learn from the way you organised your activities? What can you learn from your project that you could use for consecutive projects and actions?

While monitoring is about checking whether the project is executed according to plan, evaluation is about the very reasons why you’ve developed your project in the first place. Do the results of your project effectively lead to the desired change in the lives of your beneficiaries? Was your intervention strategy effective? What are the expected and unexpected effects and impact of your project? What can you learn from the way you organised your activities? What can you learn from your project that you could use for consecutive projects and actions?

Evaluations can be:

- Internal evaluations: conducted by the organisation itself.

- External evaluations: conducted by an external evaluator, either an individual or a (specialised) organisation or firm. Often donors will require you to do external evaluations because they are supposedly more independent and reliable. On the other hand, external evaluators may not understand the situation as well as the local staff or partners do. Often, time and financial constraints also weigh on the quality of the evaluation and many evaluators rely heavily on the project team anyway, which beats the point of independency (also in the end it is the NGO that pays the bill).

Projects with a long duration often have mid-term or several intermediary evaluations in addition to the final evaluation. In order to do a good evaluation, the evaluators need access to information from the monitoring system. One of the most common problems is that no baseline situation has been established at the onset of the project, making it difficult to appreciate the evolution of the project and of the situation of the beneficiaries.

In addition to providing an evaluation report, most evaluators will organise a feed-back meeting of some sort. This is important for people to learn about the findings of the evaluation and the good things and bad thing about the project. This way they can take the information along for the next project.

PCM in practice

Where the Logical Framework Approach (LFA) is all about getting the point of view of the stakeholders to define the project, PCM focuses more on the project manager. It is not surprising that this method became popular in large organisations and donor institutions. PCM is a good method of managing multiple projects at once, seeing to it that they comply with the overall strategy of the organisation and respond to the right procedures and rules.

For smaller organisations with fewer projects, PCM may seem more of a burden than a benefit and not worth the overhead. However, PCM does show us that there is more to development than just doing activities with your beneficiaries. You do need an idea where you are going in the long run, and your projects should all originate from a common sense of direction. Otherwise you’ll just end up with a whole bunch of different activities that are difficult to manage (and fund). There are plenty of organisations that ended up in that situation.

PCM also forces you to reflect on what you will do when things don’t go as planned, and allows you to learn from these experiences. It acknowledges that the environment you work in is constantly evolving, which means that you must be flexible and capable to adapt.

Learning from you successes and failures is equally important. Just trying to do good is not good enough. Your beneficiaries have a right to get quality assistance and to get the best you can deliver. International development and the fight against poverty, disease, inequality are complicated domains that need more than well-meant amateurism (although professionals can also learn from the enthusiasm and the good spirit of small volunteer actions).

The idea of the learning cycle in PCM is a solid one. It also teaches us to check what we do and react, in other words to be flexible in the execution of our projects. However, we all know that theory and practice are sometimes far apart. PCM is also an approach that favours standardised procedures and models, which lead to rigidity and to (huge) administrative overhead. PCM is a simple model that facilitates project management, but this very simplicity also pushes people to oversimplify complex development situations. As with LFA – which it incorporates – the rigid cause-and-effect logic forces people to leave out important parts. Especially when combined with rules such as ‘a maximum of one specific objective / project purpose per project is allowed’.

On the other hand, PCM has been used to manage enormous and complex programmes that combine actions in many countries and regions all over the world, over long periods of time. In these cases, the overall programme regroups specific actions and sub-actions in different places at different moments. To manage such complex programmes, you need a project management approach that goes further than that of a simple individual project.

Whose Project Management Cycle?

As we’ve mentioned before, Project Cycle Management is not always very popular. This has something to do with the fact that it has been pushed very much by the donor community. NGOs were forced to apply this approach and were faced with a plethora of complex rules to obey and models to fill out. In turn, NGOs in developed countries forced their partners in the developing countries to respect the rules and formats.

The net result of this very top-down process is that even very small and weak local organisations are forced to use very complex and cumbersome models for monitoring and reporting. So in the end, you can ask yourself whose project management cycle we are talking about. One could argue that it is all about the donor’s project management because they call the shots and force everyone to use their models and respect their procedures. As a consequence, NGOs (both in North and South) have a tendency to look for the information that is requested by the donor, not the information that is necessary to develop a quality project. Although PCM makes use of the participatory techniques of the logical framework approach, some needs of the beneficiaries may be get neglected because they don’t fit the templates.

NGOs, both in North and South, should be aware of this danger and avoid assimilating (or being assimilated by) the donors’ project management approach. Instead they should develop their own management cycle, making sure that they are able to deliver the necessary information, but without becoming totally dependent on the donor. On the positive side, these models and procedures often do provide a valuable service because they are a solid and practical framework. But NGOs both in the North and South do have to ask themselves whether they are managing their own project cycle, or whether they are a subsidiary of the donor or the partner organisation that has access to the money.